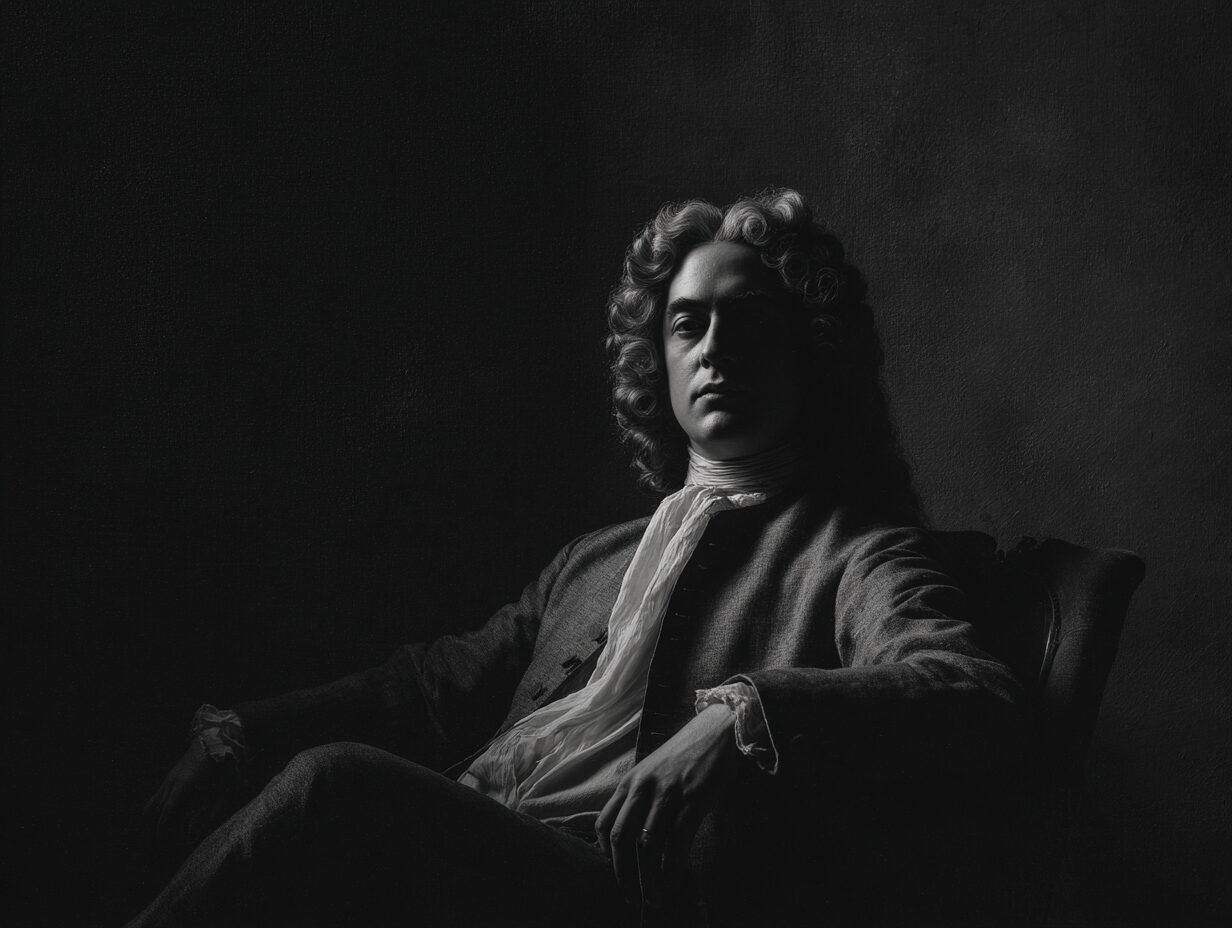

Everybody knows Handel’s Messiah, probably one of the most performed classical works of all time. Every Christmas, it echoes through concert halls worldwide ad nauseam —yet we keep returning. Few, however, know the history behind it.

Handel moved to England not merely to compose but to become an entrepreneur. He dedicated much of his life to producing operas and serving the monarchy, yet he couldn’t achieve the success he sought. Au contraire, he poured his efforts into Italian opera at precisely the moment English audiences were losing their taste for it. By the 1730s, declining ticket sales, fierce competition, and a ban on Lent performances pushed his company toward bankruptcy.

In April 1737, his company collapsed. That same month, at age 52, Handel suffered a stroke that paralyzed his right arm. He even practiced in the dark to avoid being seen at home — so he could feign absence if creditors came knocking. Broke and weakened by the stroke. Nowhere to go. He was 52.

Four years later, still struggling financially, he received a libretto from Charles Jennens — a wealthy landowner who had compiled passages from the King James Bible tracing the prophecies of the Messiah, Christ’s birth, death, and resurrection. The text was not dramatic in the operatic sense; there were no characters to impersonate, no direct speech. It was pure meditation. Handel, a faithful Christian, recognized something in this structure. He began composing on August 22, 1741, and finished on September 14 — just 24 days for a work that runs nearly three hours.

What Handel created was formally remarkable. The Messiah contains no arias in the conventional operatic sense — no virtuosic display for its own sake. Instead, Handel built something between oratorio and sacred cantata: a work where chorus, recitative, and aria serve the text’s contemplative arc rather than dramatic spectacle. The orchestration is deliberately restrained, allowing the words to breathe. And in the spaces between movements, Handel composed silence — pauses that let the weight of scripture settle before the music resumes.

Messiah premiered on April 13, 1742, in Dublin at the Great Music Hall on Fishamble Street. The venue held 600; over 700 attended. Ladies were asked to forgo their hoop skirts, and gentlemen were asked to leave their swords at home, all to make room. The performance raised £400 for charity and secured the release of 142 imprisoned debtors. The London premiere followed on March 23, 1743, at Covent Garden, though it met initial controversy — some clergy objected to sacred text performed in a theater. Handel avoided the word Messiah in advertisements, billing it simply as “A Sacred Oratorio.”

Though conceived for Easter and premiered during Lent, Messiah became a Christmas tradition — particularly in America, where the Handel and Haydn Society gave the first complete U.S. performance on Christmas Day 1818 in Boston. Part I’s prophecies of Christ’s birth, including “For Unto Us a Child Is Born,” aligned naturally with Nativity celebrations. Today, December performances dominate, from sing-alongs to orchestral events, though Easter and Lent performances persist in Britain and elsewhere.

After Messiah‘s success, Handel rebuilt his fortune through oratorios, which required no elaborate staging or costumes. He proved to be a shrewd investor as well. Bank of England records show he had bought South Sea Company stock around 1715 and — crucially — sold it between 1717 and 1719, just before the catastrophic bubble burst in 1720. Whether luck or intuition, he avoided the crash that ruined Isaac Newton and countless others. From 1743 until his death, Handel steadily invested his performance earnings in government annuities. He died wealthy in 1759 at age 74, leaving approximately £17,500 in Bank of England holdings (worth over £2 million today), much of it bequeathed to charities, the Foundling Hospital, and family.

You cannot know what life holds, nor the turbulent paths it will take. Handel’s story offers something for those in difficult seasons, especially when the weight of time makes setbacks feel permanent. Only God knows what lies ahead. Our duty is to keep walking.

S.D.G.