Years ago, I embarked on a music project called Omega Code. We made modest progress as a group, but the project ultimately stalled. The primary reason was pragmatic: I realized that advancing to the next stage would require a disproportionate investment of time and energy—one that would threaten my livelihood. To turn it into a sustainable primary source of income, I would have had to make it the center of my professional life. I chose not to. Instead, I brought the project to a close, leaving it as a vivid memory rather than a career. I focused on Combustion Studio instead.

Despite its brevity, Omega Code became an unexpected apprenticeship. It taught me valuable lessons about the music industry, including the importance of collaboration and leadership, as well as the interplay between aesthetics and creativity. Much of our sonic experimentation was driven by visual inputs, a synesthetic approach where imagery shaped sound. Being deeply immersed in the creative field, I benefited from the contributions of many collaborators who subtly shaped the project.

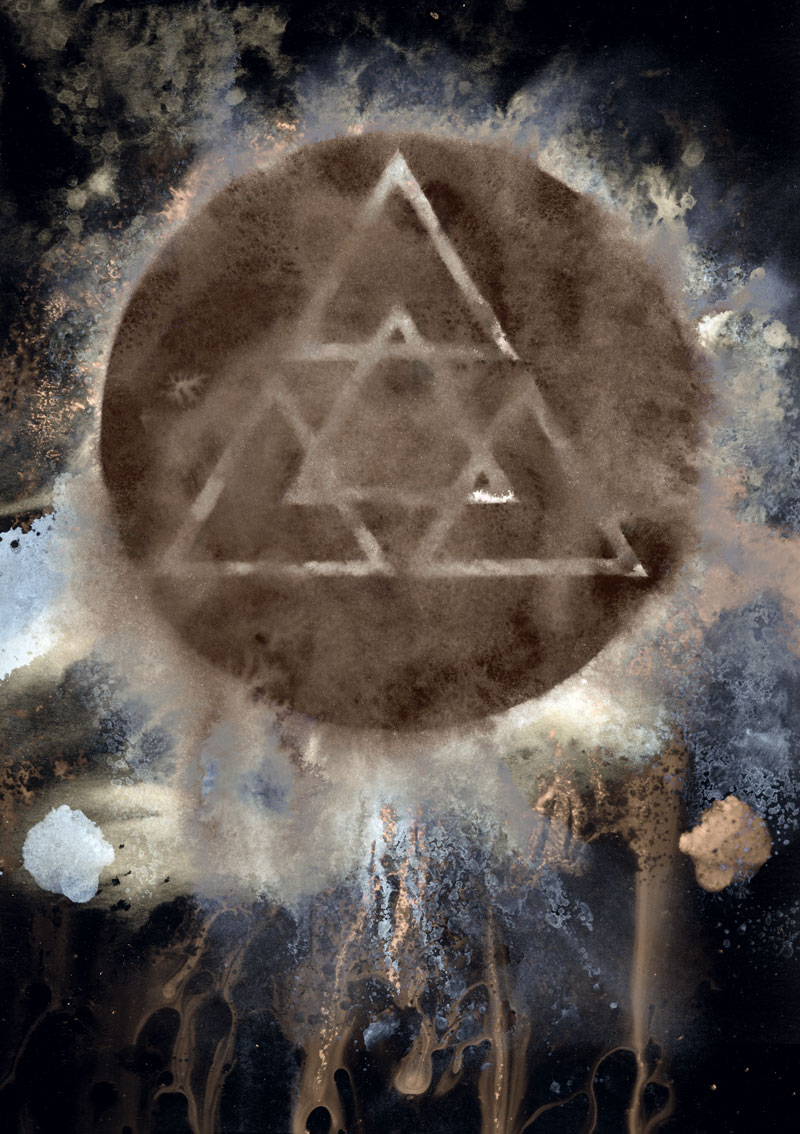

One of the most surreal aspects was the global reach of our visual campaign. Before we released a single track, a series of poster designs sparked international attention. The project existed as an MVP (minimum viable product), yet people engaged as if it were a cultural artifact. We received over 500 illustrations from around the world; designers used our template to generate their own variations. The triangular motif we used triggered a brief design trend in 2009—a slight fever that seemed disproportionate to our scale.

The triangle puzzled many: Why a triangle if the name was Omega Code? Our symbol, inspired by the Christian Trinity, was less a literal reference to “omega” than an emblem of the project’s philosophical roots. As Jungian psychology might suggest, symbols carry meaning beyond logic, surfacing archetypes that resonate collectively with others.

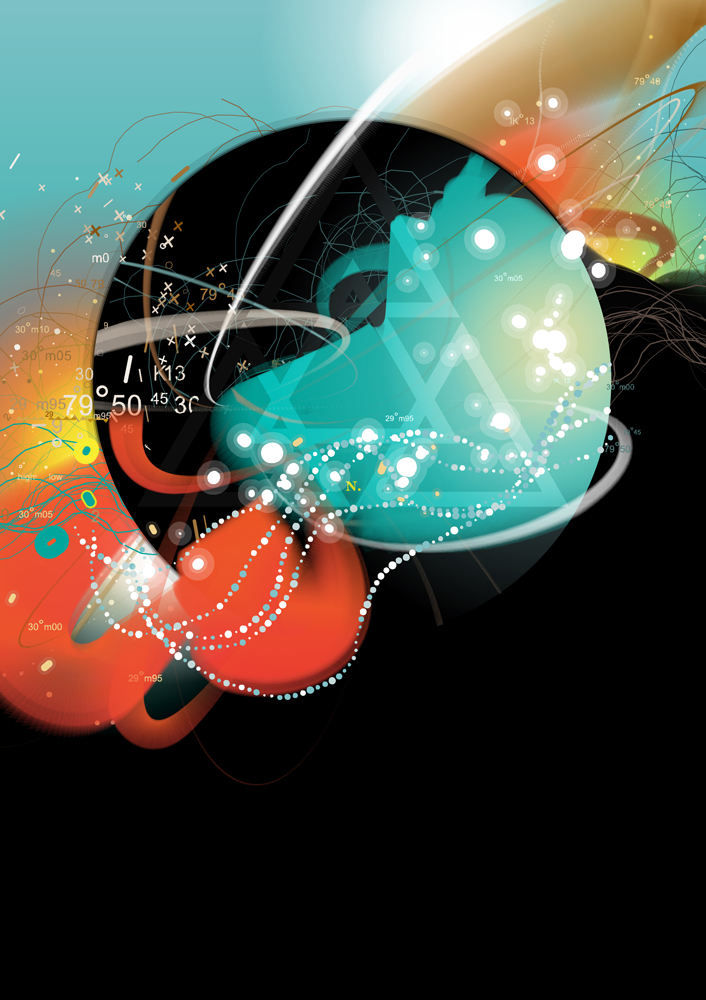

A decade after closing Omega Code, we now find ourselves in the midst of the AI surge. Its influence reaches across disciplines. While many express concern over potential disruptions, I regard this era as an unprecedented opportunity. For the first time, ideas themselves—not just final products—are becoming effortless to manifest.

Back then, many of my conceptual ideas remained unfulfilled because they demanded budgets I didn’t have. Today, a well-crafted prompt can breathe life into concepts that once seemed unattainable. When ideas are grounded in coherent principles, aesthetics, and personal vision, AI becomes a tool to overcome what Jung called the “archetypes of the collective unconscious.”

Prototyping—once a luxury—is now accessible to anyone with curiosity. Since the early 2000s, the internet democratized creativity; today’s AI tools amplify that democratization exponentially. This is neither optimism nor pessimism; it is simply an acknowledgment of historical momentum.

Even brief engagement with old Omega Code concepts recently yielded results that were unimaginable at the time—3D experiments, photographic mock-ups, and even musical sketches. Yet there remains a danger in assuming that AI will deliver finished work. As the painter Chuck Close once said, “Inspiration is for amateurs; the rest of us just show up and get to work.” Technology offers tools, not miracles; the art still requires discipline, hard work, and human intention.

Were Omega Code to arise today, it would sound and look entirely different, shaped by new tools and cultural currents. My intention in revisiting it is not nostalgia but an invitation: to emphasize ideation and hands-on creation—to remind us that tools alone do not make the artist.

”“Inspiration is for amateurs;

Chuck Close

the rest of us just show up and get to work.”

We achieved amazing results with the Omega Code project, particularly through the collaboration of talented artists who contributed to the posters. Notable individuals involved included Joshua Davis, Mike Cina, Nelson Balaban, Tom Muller, Robert Lindström, Michael Paul Young, and Motomichi Nakamura, among others. Gabriel Wickbold took the final photograph for the album cover, while Brendan Duffey, known for his work with Bruce Dickinson, Sheryl Crow, and Kendrick Lamar, handled the album’s mastering. Still, the effort required to bring this project to life was significantly greater than what is typically needed today.

One should take advantage of the zeitgeist rather than be overwhelmed by it.

There are no excuses for being idle.

– On Symbols & Archetypes:

– Carl Jung, Man and His Symbols (1964): “The creation of something new is not accomplished by the intellect but by the play instinct acting from inner necessity.”

– On Creativity & Labor:

– Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, Creativity: Flow and the Psychology of Discovery and Invention, for the concept of “flow” in creative work.

– On Technology & Art:

– Walter Benjamin, The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction — for historical parallels between earlier tech shifts and AI.

– On Prototyping & Design:

– Eric Ries, The Lean Startup — for the concept of MVP as applied to art and music.